Recently, I attended the National Association of Independent Schools Annual Conference in St. Louis. I was excited to go because (1) it was my first time to present at NAIS, something I had been wanting to do for a long time, and (2) I was eager to hear from others, in person, about how they as school leaders, instructors, and industry consultants were making sense of and responding to the recent, ubiquitous success of 2nd Wave, generative AI technologies. Full disclosure: I too was presenting on that same subject, along with Dr. Brett Jacobsen and Josh Clark, in a session titled, “Are You AI Ready? A People-Centered Systems Thinking Approach.”

In almost every session and conversation I participated in, the focus quickly (and understandably) became one around questions of AI *policy*, a word which Google defines as “a course or principle of action adopted or proposed by a government, party, business, or individual.” In other words, policy, as defined here, serves as a mechanism for making the right decision in a near or distant future predicament. However, something as complex and unpredictable as AI begs us to ask: What if there are no clear, right answers? What if AI is so fluid in its current emergence that no policy can possibly predict any and all plausible and possible scenarios? In those cases, our policies, like early AI technologies, may turn out to be brittle tools, and the old adage that “policies are meant to be broken” once again proves probable, if not inevitable.

With that said, what would be a better approach to this conversation? Or put differently, what’s an alternative mental model we might use, other than a policy-minded approach, to expand our perspective on how we might act on and respond to opportunities and challenges presented by AI, both in the immediate and more distant future?

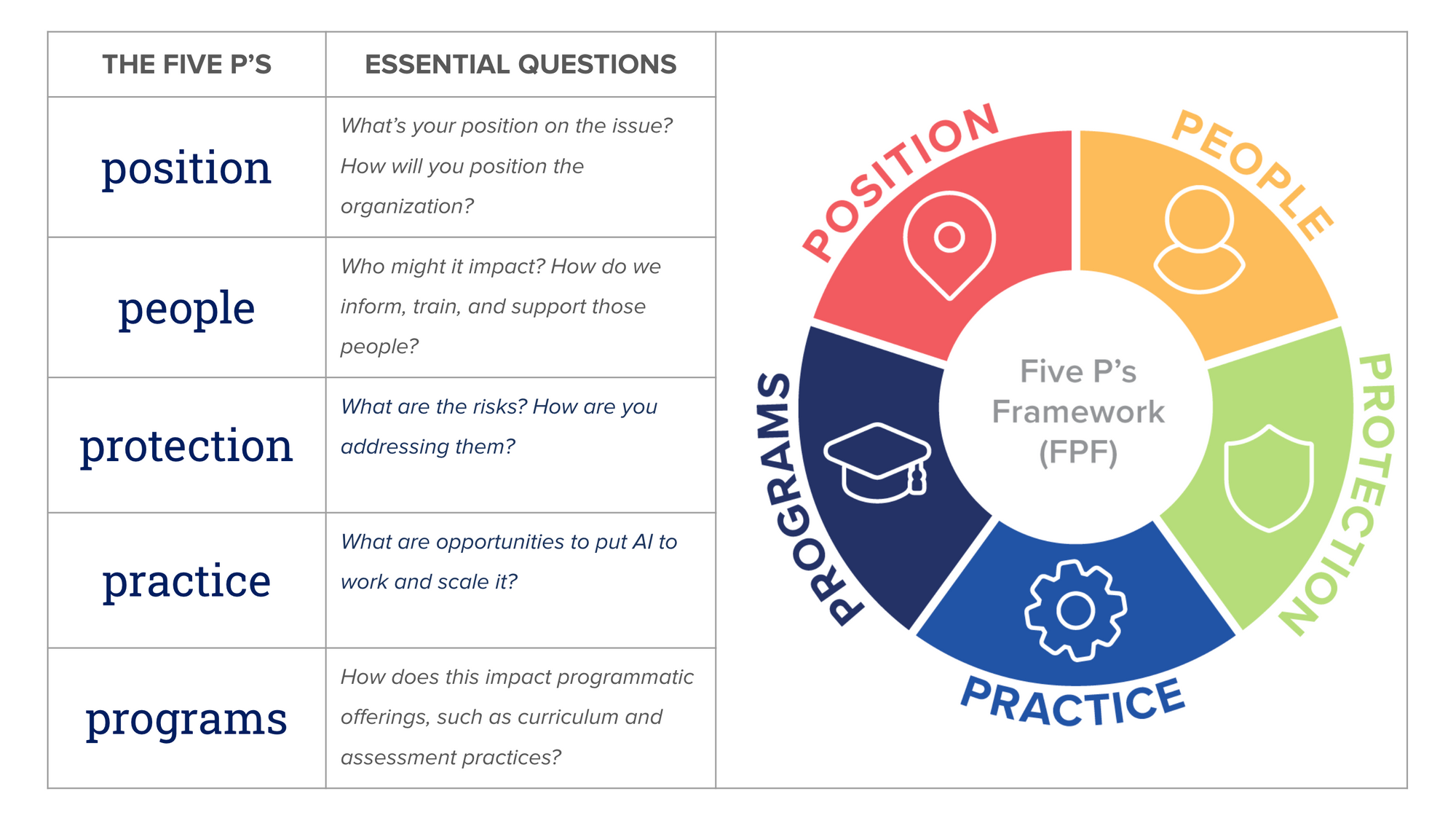

At MV Ventures, we introduced the 5 P’s framework for understanding the probable, plausible, and possible implications of AI on our institution’s people, protection, practices, and programming to shape an alternative mental model for grounding our position, not policy. How we understand these implications does less to carve out specific, prescriptive policies for AI’s use (or prohibition thereof) and more to help us determine a robust, strategic positioning, one that’s ready for all possible opportunities and challenges.

Demands for policy are born out of a school of thought (or mental model) that operates from a certain assumption about how businesses and organizations should develop strategy when thinking about future challenges and predicaments. Kees van der Heijden in his book, Scenarios: The Art of Strategic Conversation, writes, “Over the years, three schools of thought have arisen to interpret the way managers and entrepreneurs think about their daily business [and strategy]. These can be characterized as rationalist, evolutionary, and processual” (23). The call for policy in the face of AI’s unpredictable power and impact is the kind of call that is born out of a rationalist school of thought or mental model.

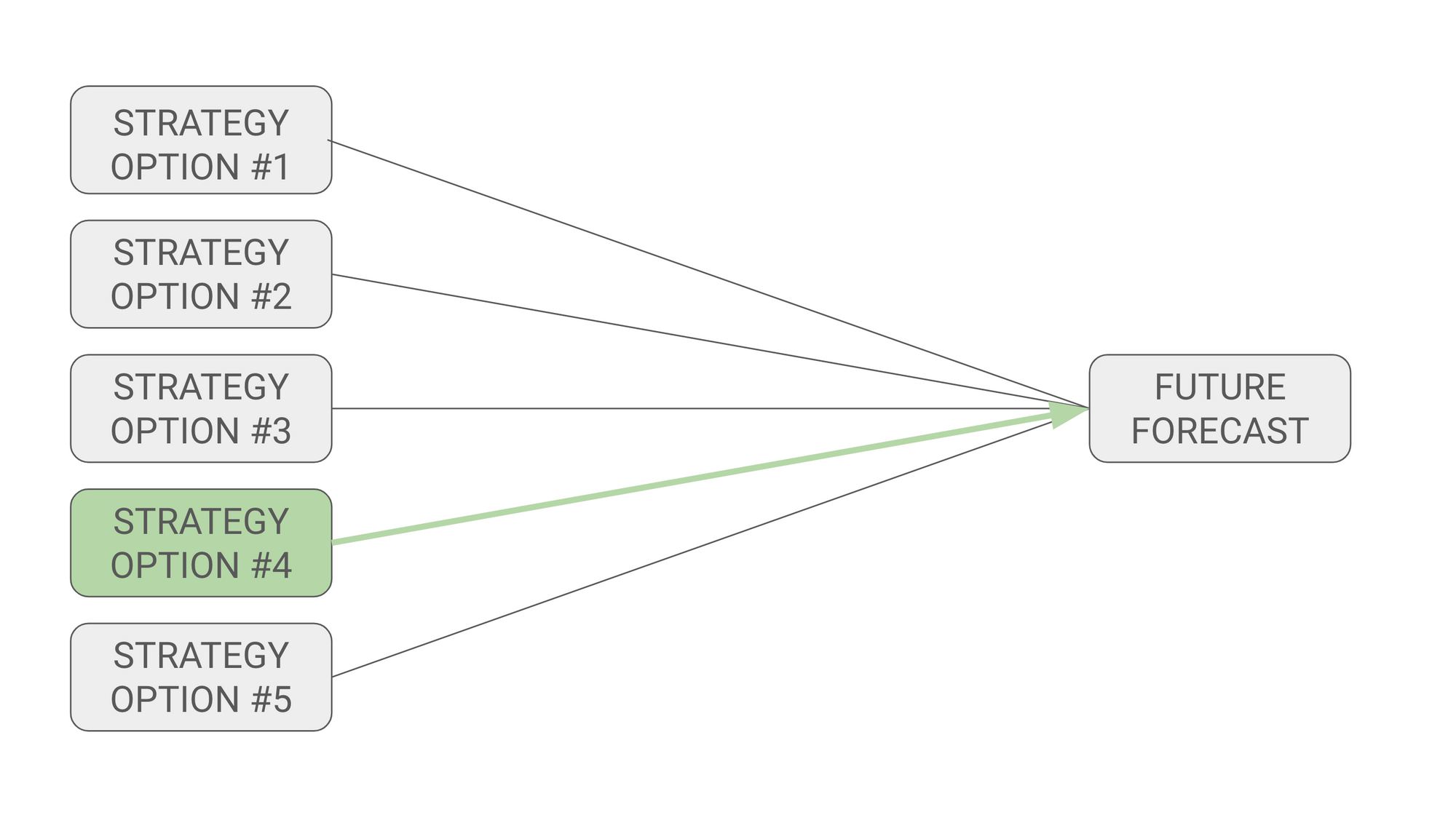

The rationalist manager or planner treats “strategy as a process of searching for the maximum utility among a number of options,” which is predicated on assumptions like: the future is predictable to some degree; there is a single, best answer in most situations; or people will act rationally in future situations (23-24). In order for us to search, with confidence, for maximum utility when faced with future challenges, we have to have a pretty good notion of what the future will look like and be able to predict, with accuracy, various actors’ actions and reactions. If we can assume as much, then forecasting the likely future for purposes of developing the best policy makes sense as an approach, but keep in mind that “the assumption underlying forecasting is that some people can be more expert than others in predicting what will happen, and the best we can do is ask them for their considered opinion of what might be in store” (27).

If AI policy is our demand, then we risk demanding it on these terms with the kind of assumptions we just mentioned, which leads me to ask: Who are those experts? Where are these expert systems (to put it in AI terminology) or Delphic oracles that can help us identify our optimum policy for AI use and adoption in our schools? Who has the forecast we need for this?

Even if we find some oracle-like experts, here’s the risk to that approach:

- Complexity eats expertise for lunch every single day.

- The future cannot be predicted because the future does not exist. (Jim Dator’s 1st law of futures work)

- We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us. (Jim Dator’s 3rd law of futures work)

AI is complex, so proposition #1 is relevant, and we don’t know the future, so forecasting from a rationalist perspective will always be a gamble. And sure, we shape our tools and models for crafting strategy, but they determine in return what we see and amplify versus what we overlook or ignore.

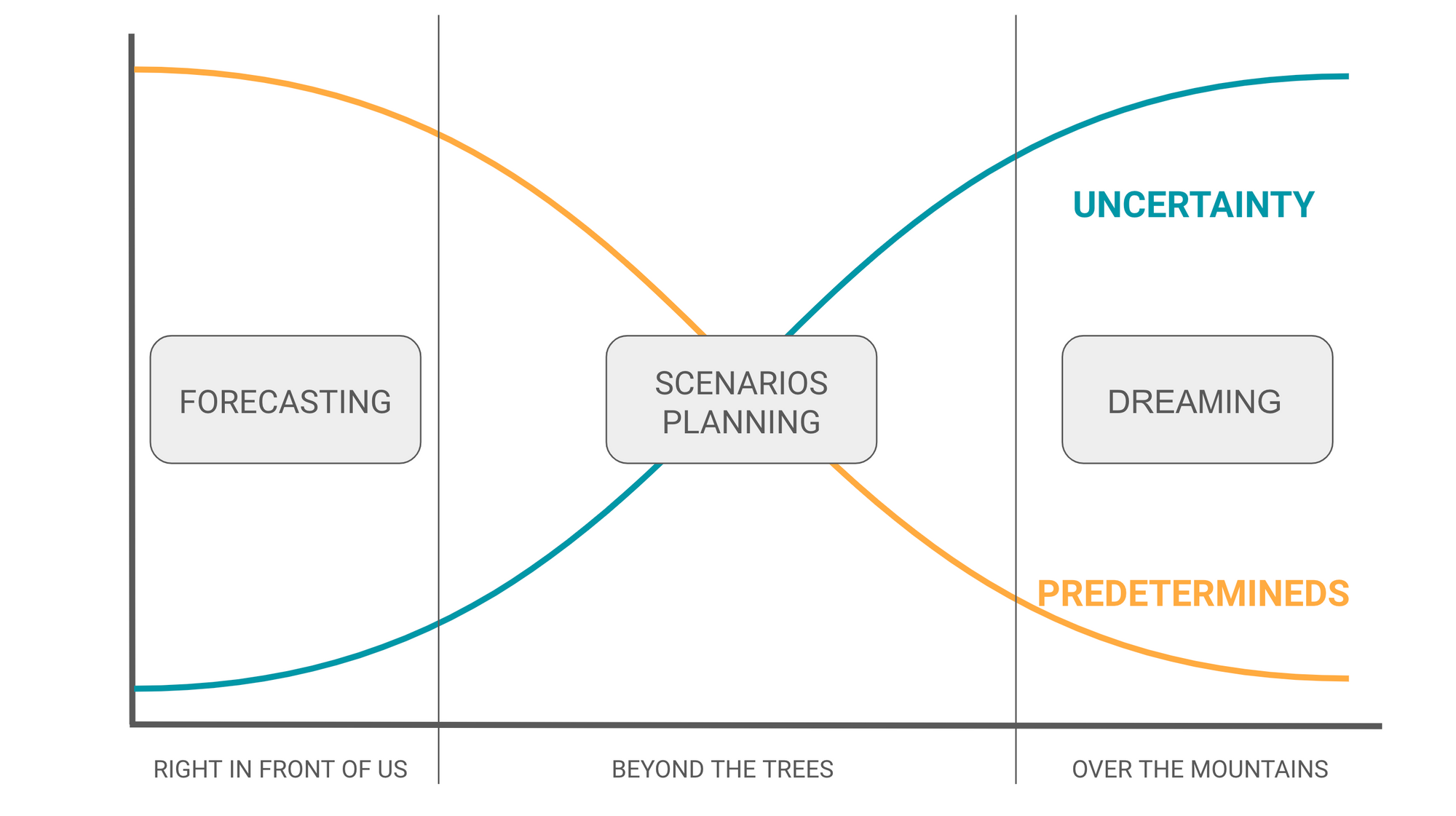

It’s important to keep in mind, however, that “we have to forecast. We couldn’t drive a car [at night or in a storm] with the lights switched off altogether. The important thing is to realize the limits of our view. Making predictions beyond our capability to forecast lies at the bottom of the crises of perception” (90). Forecasting works well when dealing with known risks in the immediate future, and therefore we should engage in that kind of work. But when faced with “structural change” or “structural uncertainty,” forecasting (and the “right answer policies” that follow it) could lead to a “crisis of perception” or the “inability to see an emergent novel reality by being locked inside obsolete assumptions” (31).

I think it’s safe to say that AI is exactly the kind of “emergent novel reality” that brings new structural uncertainties to our schools and beyond, structural uncertainties that no oracle or expert system could predict with complete accuracy. That’s why the topic demands a systems-thinking approach (like the 5 P’s framework), or a new mental model that stretches us to perceive more than what forecasting and policy-making can afford us.

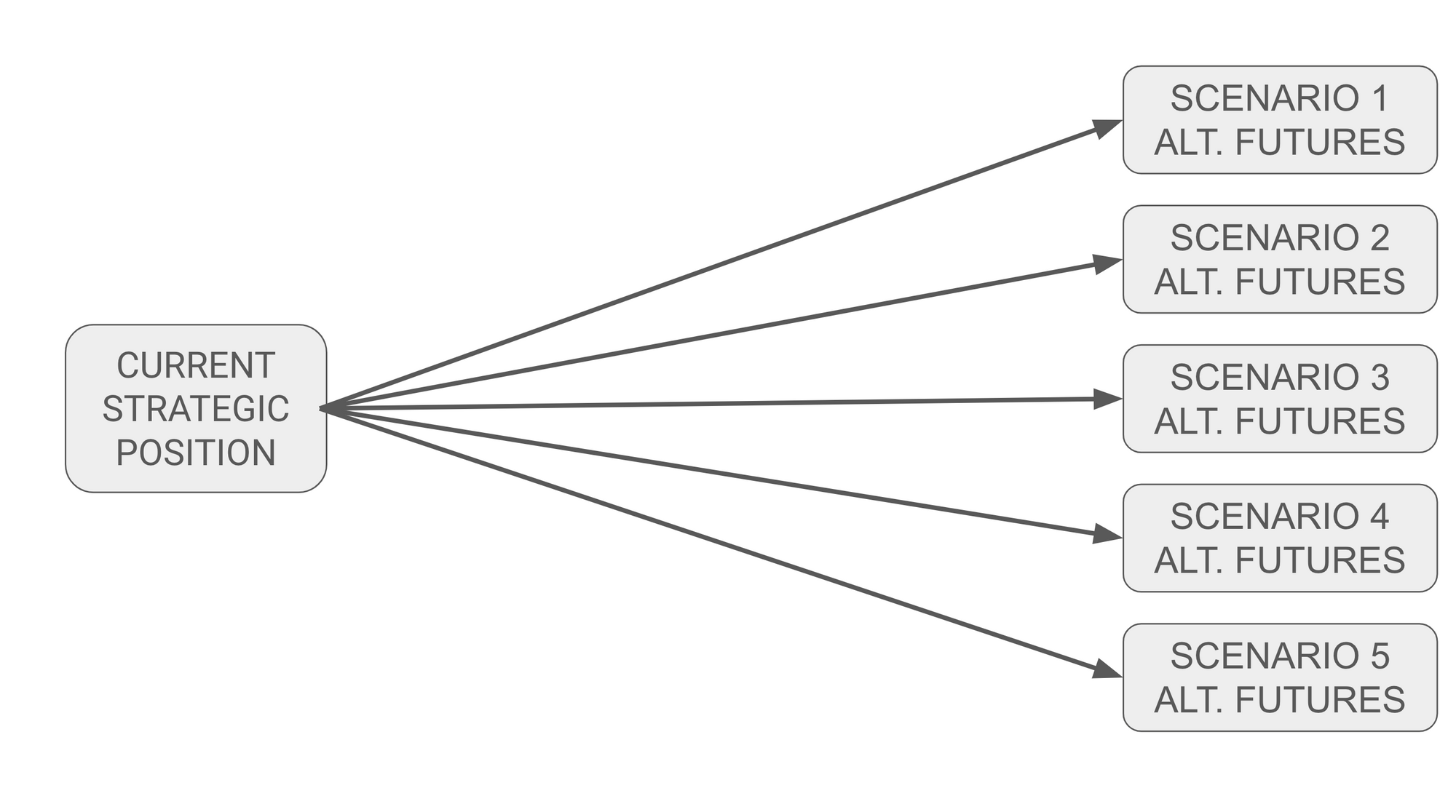

What we need is a processual, scenarios-based approach that expands our foresight, as opposed to narrowing our forecast. “Scenarios are not seen as quasi-forecasts,” writes van der Heijden, “but as perception devices… Scenarios are a set of reasonably plausible, but structurally different futures. These are conceived through a process of causal, rather than probabilistic thinking… Scenarios are used as a means of thinking through strategy against a number of structurally quite different, but plausible future models of the world” (29). Because scenarios are multiple, equally plausible, and neither good nor bad, they help us develop a mental model and mode of “scenaric perception” such that we can “react flexibly to structural change” in a variety of contexts or lived realities (31).

Unlike forecasting, scenarios-planning is not prescriptive, nor does it reduce or eliminate irreducible uncertainties. Also, it welcomes diverse views, all for the purposes of determining a current position that maintains “the scenaric stance,” or “a state of constructively maintaining multiple states of possibility in mind at the same time – considering, processing, evaluating, and being ready” (Smith 4). This is why Scott Smith says that foresight work or what he calls “futuring” is “ about understanding the landscape of potential futures in such a way as to guide better decision making in the present” – a decision making that comes less from policy and more from teams who understand the present in terms of multiple, equally plausible futures (Smith 104). And the decisions that are eventually made are driven not by the idea that we can link the best policy to the most probable future but by the desire to position one’s organization in a way that, no matter which plausible future unfolds, the stakeholders are ready to play a part in strategically shaping the unpredictable future that ends up being the case with the hopes of influencing that future toward preferable outcomes.

Kees van der Heijden emphasizes over and over that, “While forecasts are decision making devices, scenarios are policy development tools” (57). But the more I think about what we mean by policy, the more I want to suggest, humbly of course, we alter his point to say that “scenarios are tools that help us develop a more strategic, agile position.” What we need with AI is not policy, but a robust, agile, values-informed position that can respond to any of the myriad futures that await us near and far. Otherwise, we may find ourselves in the midst of a crisis of perception as the world of AI technology only continues to accelerate.

As stated, rationalist forecasting does have its place, especially if we add the dimension of time. There are things right in front of us, that are probable, that need our care and attention, that therefore warrant some rationalist forecasting – like the use of Deepfakes among peer groups in school. Then there are things that are a little more beyond the trees, like the development of real-time, human-level language translators, where it warrants our thinking through multiple, plausible scenarios to improve our practice and position in World Language instruction right now.

A simple example from the field

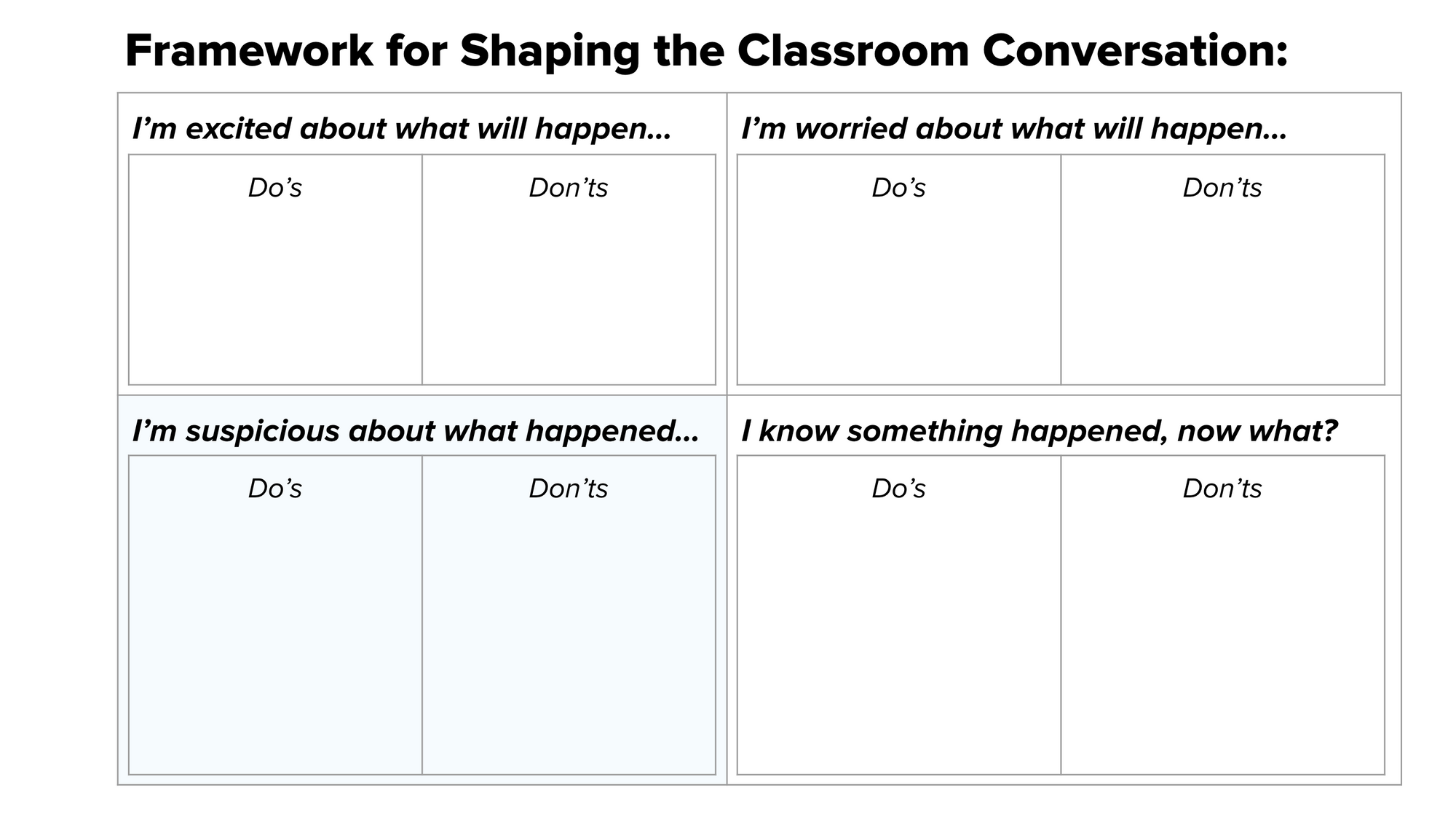

When teachers approached me in January 2023 about developing an AI classroom policy, I refused to take a rationalist, one-policy-catch-all approach, and instead tried to create a tool for developing a position that assisted multiple scenarios and multiple users, which led to the following framework:

As teams we workshopped the tool, developing do’s and don’ts nudges for three possible scenarios: (1) early adopters who were excited to accelerate the experimental use of AI in their classes; (2) skeptics who rightfully worried about an accelerated adoption of AI technologies; and (3) teachers who suspected that AI was used in a way that compromised the integrity of the inquiry process. None of these scenarios needed a singular, if-then policy per se; what they needed were tools and maneuvers that honored our schools’ values and mission as a place of “inquiry, innovation, and impact” while supporting a teacher’s classroom system in the context of multiple, plausible situations. The only place where traditional policy lives in the showcased tool is in the bottom right quadrant (I know something happened, now what?), and what we discovered is that the policy already existed: the age-old (not emergent) issue of academic honesty. We didn't need new policy, but we desperately needed to think through plausible scenarios to better define our values-informed position in the now.

Sources:

- Badminton, Nikolas. Facing our Futures: How Foresight, Futures Design, and Strategy Creates Prosperity and Growth. Bloomsbury, 2023.

- Smith, Scott. How to Future: Leading and Sense-Making in an Age of Hyperchange. Kogan Page, 2020.

- van der Heijden, Kees. Scenarios: The Art of Strategic Conversation. Wiley, 1996.

Comments