Why are so many kids, despite our best efforts, not all right when it comes to behavioral health and wellness?

Is our interdependent connection to nature an example of what we fail to account for when attempting to nurture a learner's wellness, identity development, and grounded sense of purpose?

And what if Artificial Intelligence could play a role in all this? What if the recent popularity and success of AI could help us knock loose a new way of thinking "which seeks to override our human tendency to separate ourselves from the natural world"?

Transforming Schools While Breathing Under Water: Aquaman Learns About Physics

Let's start with a thought experiment.

Picture the iconic comic book hero, Aquaman, but this Aquaman has never been to the earth’s surface; he doesn’t even know that he is underwater.

One day, however, our aquatic, humanoid friend finds a book in a sunken ship at the deepest depths of our ocean’s floor: let’s pretend that the book explains the physics of how gravity works (gravity under normal conditions on the earth’s surface, of course), and using that textbook, Aquaman begins to learn about the predictable motions of objects due to gravitational force.

However, nothing seems to add up when he tests the theory or law in his normal, environmental circumstances, because our Aquaman fails to realize or see that he is immersed in and connected to an aquatic environment that is an integral factor for how gravity actually works in his underwater, lived experience.

Sometimes I feel like this when seeking, collectively and collaboratively, to improve so much about the school experience.

Sometimes it feels like things just don't add up the way we want them to when we attempt to apply theories, best practices, or purported “laws of educational physics” to how we run schools and help kids. Take behavioral health and wellness, for instance: our unprecedented crisis of rising rates of depression and anxiety among kids in today's educational institutions (Abrams 2023). Take the fact that so many kids report a sense of purposelessness in our schools and our beyond (Lavasseur 2021). Could the theories and best practices we use to address such a crisis be failing here, not because the theories are wrong, but because we are employing them in a context where we’re ignoring an integral factor that makes this all make sense? Is there some kind of water-like substance in the ether of schooling that we're not accounting for as we float theories, solutions, and intervention plans that just don't seem to be delivering like promised? What is that substance or factor?

In Aquaman’s case, it was the all-encompassing presence of literal water as a physical-material factor impacting the physics of his daily practices. It's no surprise he's frustrated, or resigned to the idea that his newfound physics textbook is total baloney. He doesn't see nor understand the complete reality of his water-immersed environment and his interconnected place in it, which begs the question...

Nature and Cities: Plato's Phaedrus and the Cosmopolitan Animal

In Plato’s Phaedrus, (a text I’ve written about here, here, and here) Socrates proclaims quite confidently, “... I’m a lover of learning, and trees and open country won’t teach me anything, whereas men in the town do” (250D, emphasis is mine). Stated after his interlocutor, Phaedrus, urges Socrates to accompany him for a discussion outside the city walls of Athens, Socrates offers this interesting juxtaposition or binary – an opposition of cities versus nature – as if cities exist completely separate from nature, which of course further suggests that humans, in some way, are set apart from nature as well, particularly when it comes to learning and intelligence.

I think of Melanie Challenger’s book, How To Be Animal: A New History of What It Means To Be Human, where she announces, “The world is now dominated by an animal that doesn’t think it’s an animal. And the future is being imagined by an animal that doesn’t want to be an animal. This matters” (1). It matters because the human animals we’re talking about “are agents of evolution with far greater powers than sexual selection and selective breeding,” because the human advantage, as Socrates implies, really is our capacity for learning quickly and more deeply. It’s why Stanislas Dehaene describes us as Homo docens, “the species that teaches itself,” writing, “Natural selection, Darwin’s remarkably efficient algorithm, can certainly succeed in adapting each organism to its ecological niche, but it does so at an appallingly slow rate… The ability to learn, on the other hand, acts much faster – it can change behavior within the span of a few minutes, which is the very quintessence of learning: being able to adapt to unpredictable conditions as quickly as possible” (xix).

We have the capacity to adapt and even change the course of evolution, not just for us, but for our entire interconnected environment in the natural world, an amazing but also frightening capacity, especially if we are in denial about our own animal identity. As we've entered the anthropocene era, we pretend like we’re not even swimming in the same waters, like human culture and the natural world are islands apart. A human-centric view, for sure, but it's not a learner-centered one, and I think the kids are catching on to this.

Challenger's provocation is a response to our Greek philosophical legacy, a legacy that learners are no longer buying. They're reading social media headlines, following influencers like Greta Thunberg, and starting to take seriously our place on the planet, and if we as school leaders don't take seriously our interdependent role of influence in the “thicket of life” we call nature, the younger generations will detect the gaslighting (whether it's intentional or not), exposing them to greater likelihood of alienation and disconnection.

Like Challenger said, our place in nature matters, and I believe it matters as well when talking about depression and anxiety rates among the youth, when thinking about their sense of belonging and connectedness. A connectedness that is always already entangled with our natural world. Yet, as the planet reveals its pain to us, society spends more time celebrating the fantasies of billionaires who dream of colonizing Mars, when we should be talking about how to build, together, in our entanglement, regenerative communities of sustainability and belonging.

On Turning Outward

As "moderns" we've done a decent job of turning inward (and we should) when addressing health and wellness, but we more often forget the need of also turning outward by valuing, nurturing, and taking seriously our integral, interdependent connection to the natural world that, contra Socrates, we are inseparably apart of, which beckons us to ask:

If so, we need “a [new] way of thinking,” writes James Bridle, “which seeks to override our human tendency to separate ourselves from the natural world… Conventional terms such as ‘the environment’ and even ‘nature’ itself (particularly when opposed to ‘culture’), compound the erroneous idea that there is a neat divide in the world between us and them, between humans and non-humans, between our lives and the teeming, multitudinous living being of the planet” (17). How might we learn to think and see our connectedness anew, to leverage that connectedness to learn more deeply about ourselves and live healthier lives, and to understand that our connectedness is the ground upon which we design a better (more-than-human) world?

And what if Artificial Intelligence could play a role in all this? (Yes, you read that right.) What if the recent popularity and success of AI could help us knock loose this new way of thinking "which seeks to override our human tendency to separate ourselves from the natural world"?

Seeing the Magical and the Spiritual: A New Kind of "Multiple Intelligences"

Lots of recent literature on generative AI tends to fret and wonder about humanity's significance in the wake of technology's most recent demonstrations of brilliance. If we're no longer the smartest agents, where does it leave us as a species?

But what if we're missing out on another opportune perspective, namely, one that sees AI as a means for reconnecting with the natural world, as an entry point to belonging to something greater and more-than-human?

To understand what I mean, consider the case for making learning and inquiry in schools a more spiritual endeavor – a spirituality, however, that is not anthropocentric, but magical in nature. Just bear with me.

Many indigenous spiritual practitioners, according to David Abram, often claim a kind of magic – a capacity best defined as “the ability or power to alter one’s consciousness at will” (9). He writes, “The traditional magician cultivates an ability to shift out of his or her common state of consciousness precisely in order to make contact with the other organic forms of sensitivity and awareness with which human existence is entwined… It is this, we might say, that defines a shaman: the ability to readily slip out of the perceptual boundaries that demarcate his or her particular culture in order to make contact with, and learn from, the other powers in the land… Magic, then, in its perhaps most primordial sense, is the experience of existing in a world made up of multiple intelligences” (9, emphasis mine). In other words, intelligence is not just to be found in cities like Athens (sorry, Socrates); we humans are a part of something greater, something more cosmic and interconnected, a network of collective intelligence, meaning our intelligence does not separate us so much as connect us to the sensuous, living world around us. This is what I mean by rethinking our response to intelligent machines in the context of our connection to nature's "intelligences."

To illustrate, David Abram shares the story of living with an indigenous magic practitioner in Bali, residing on a family compound consisting of several small buildings for sleeping and cooking. Every morning, when staying at the compound, the Balian’s wife brought a bowl of fresh fruit to Abram while also balancing a tray with little mounds of rice; when she returned to get the fruit bowl, Abram noticed her rice tray would be empty. When asked what the rice was for, the woman responded, “They were offerings for the household spirits… gifts for the spirits of the family compound.” Abram observed that every morning, after delivering his fruit, she carefully set the rice “offerings” at the corners of each of the buildings, but he also confirmed that each rice offering was nowhere to be found upon inspection later that afternoon.

Where did the rice go?

The reason the rice disappeared, it turned out, was due to ants, several lines of them taking the different rice offerings and returning to their colonies away from the compound, a discovery that first provoked a sense of dismissiveness in Abram, until a humbler, more open-minded thought occurred to him: “What if the ants were the very ‘household spirits’ to whom the offerings were being made?” (12).

He ends the story with the following insight:

To Abram's point, intelligence is multiple, and despite what human exceptionalists will tell you, we are not the only intelligent agents, and nor should we want to be. This kind of spiritual awareness and inquiry is less about otherworldly, anthropomorphic visions of heavenly kingdoms and more about an ecological attunement and attentiveness to the interconnected world, an awareness we rarely cultivate nor tend to in our modern cities and schools, including Athens.

The Case for Spiritual Intelligence (whether "Authentic" or "Artificial"):

“For Plato, as for Socrates,” writes Abram, “the psyche is now that aspect of oneself that is refined and strengthened by turning away from the ordinary sensory world in order to contemplate the intelligible ideas, the pure and eternal forms that, alone, truly exist” (112-113). It’s why Socrates wants to remain walled up in the fortified security of human exceptionalism or, as we know it, the Athenian city-state. However, for Abram, “It is not by sending his awareness out beyond the natural world that the shaman makes contact with the purveyors of life and health, nor by journeying into his personal psyche; rather, it is by propelling his awareness laterally, outward into the depths of a landscape at once both sensuous and psychological, the living dream that we share with the soaring hawk, the spider, and the stone silently sprouting lichens on its course surface” (10). Being spiritual, in this context, is about conscious connection – about connecting to the multiple, natural intelligences and beings of the more-than-human world-network so we can understand more deeply how we might live, co-exist, and thrive in symbiotic relationships of regenerative interdependence.

And ants are no exception; they too demonstrate all sorts of forms of intelligence, as do forests, octupi, fungi, and even slime molds, if we are open and curious enough to really see it. And what's interesting, in my view, is how AI could help shift our perception accordingly, in just the right way, so we see all this interconnectedness with new clarity and precision.

Alan Turing famously asked, “May not machines carry out something which ought to be described as thinking but which is very different from what a man does?” And why stop with machines? In other words, why should we assume that thinking and intelligence are exclusively human characteristics? What if intelligence was a kind of behavior that connects us to something greater, something more cosmic, something more-than-human?

Shane Legg and Marcus Hunter define intelligence as that which “measures an agent’s ability to achieve goals in a wide range of environments” (Yonck 15). Stephen Hawking once described it as “the ability to adapt to change” (Yonck 16), and AI researchers, Gary Marcus and Ernest Davis, claim, “Intelligence is the ability to deploy novel means to attain a goal” (Marcus and Davis 30), much like computer scientist, Stuart Russell, who states, “an entity is intelligent to the extent that what it does is likely to achieve what it wants, given what it has perceived” (Russell 14). Hector Levesque writes, “...we want to say that people are behaving intelligently when they are making effective use of what they know to get what they want” (Levesque 40). And lastly, Alexander Wissner-Gross says, “Intelligence acts so as to maximize future freedom of action” (Yonck 18).

Definitions like these seem to corroborate Turing's point that there are multiple ways, beyond human biology, for intelligence (in Turing’s case, thinking) to manifest, prompting thinkers like Richard Yonck to state that “All intelligences needn’t mimic human intelligence to be considered of a high or perhaps even ‘higher’ order” (9). In fact, “...most aspects of intelligence may in fact exist on a spectrum” (15), leading Yonck to ponder the idea that intelligence may be “a manifestation of a much larger and universal process, one that is initially dependent on probability but, given the resultant emergent properties, becomes more and more capable of self-directed volition over time… As we progress from chemistry to prebiotic self-replication to single-cell life all the way to Homo sapiens, can we view each as its own emergent variation of adaptive collective intelligence relative to the precursors it evolved from?” (45). Abram seems to think the answer's yes, as he describes spiritual awareness as the ability to appreciate the interconnections between all cosmic forms of intelligence, and to leverage collectively intelligent networks for purposes of designing better, more sustainable forms of living: for instance, the Balian offerings of rice serve as a regenerative alternative to more ecologically destructive solutions like spraying pesticide all over one's natural environment to deter the ant intrusion. The Balian practitioner found a mutually beneficial solution that also honors the mutual intelligence of each agent.

For whatever reason, our Western culture, in my view, is experiencing a kind of spiritual numbness; some might even blame the effects of technology as playing a part. It's as if we're swimming in the waters of natural interconnectedness but pretending like we're an island unto ourselves, and ironically, technology (in form of AI) is besieging this mythological island of human exceptionalism, thereby threatening our status as the one and only cognitively intelligent species. And meanwhile, our planet is crying out in pain, while humans, including our young learners, feel all the more alone, even though intelligence may be the very thing that can renew our connectedness to something greater.

Intelligence swims all throughout nature, much like Aquaman in the ocean, yet nature might be the thing we keep ignoring, even though the science instructs otherwise. One study "suggests that interventions increasing both contact with, and connection, to nature, are likely to be needed in order to achieve synergistic improvements to human and planetary health" (Martin, et al., 2020). Another study suggests that "nature is a common source of meaning in people’s lives and [that] connecting with nature helps to provide meaning by addressing our need to find coherence, significance, and purpose" (Passmore and Krause,

2023). Some studies go so far as to claim "evidence for associations between nature exposure and improved cognitive function, brain activity, blood pressure, mental health, physical activity, and sleep" (Jiminez, et al., 2021).

Like Abram suggests, perhaps it's time for us to turn outward, and to see anew how we belong and connect to a natural, collective intelligence, and AI could help us with this outward-turning. As James Bridle writes, “But what if the meaning of AI is not to be found in the way it competes with, supersedes or supplants us? What if... its purpose is to open our eyes and minds to the reality of intelligence as something doable in all kinds of fantastic ways, many of them beyond our rational thinking?” (82-83). What if AI could help us see intelligence (and even the act of thinking) in ways we couldn't before, in ways that connect us spiritually and relationally to our ecological networks? And what if we saw all this as an integral part of caring for the behavioral health and wellness of our young learners?

AI, Biomimicry, and Expanding Mental Models

In their book, Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines, The Search for Planetary Intelligence, Bridle recalls walking in a forest, one connected and nourished by the mycorrhizal networks of fungi that made the forest, less a collection of individual trees, and more of an interconnected, intelligent organism that communicates, feels, and reacts in ways we may have failed to see initially. Bridle expresses their appreciation for nature, and its mycorrhizal support system, conjuring the metaphorical power of "networks" to make sense of the dynamic, organic complexity: "My sudden awareness… [of] the redwood forest…[as] a vibrant, active network beneath my feet, through which vast quantities of information as well as nutrients were passing, was not entirely new to me. It was the same sensation I experienced when beginning to understand, and bring into view, the infrastructure of the internet: the vast, planet-spanning network of cables, wires, machines, and electromagnetic signals which sustains and regulates humanity today. These microprocessors and data [centers], undersea cables and wireless transmissions are our own mycorrhizal network, interpenetrating everyday life…” (79-80). Bridle's "sudden awareness" – his sudden shift in seeing and sense-making – was sparked by emergent technology: It's an example of “technological models," in this case, the world wide web, "enabling us to better understand natural processes which don’t initially seem to be accessible to our reasoning” (238).

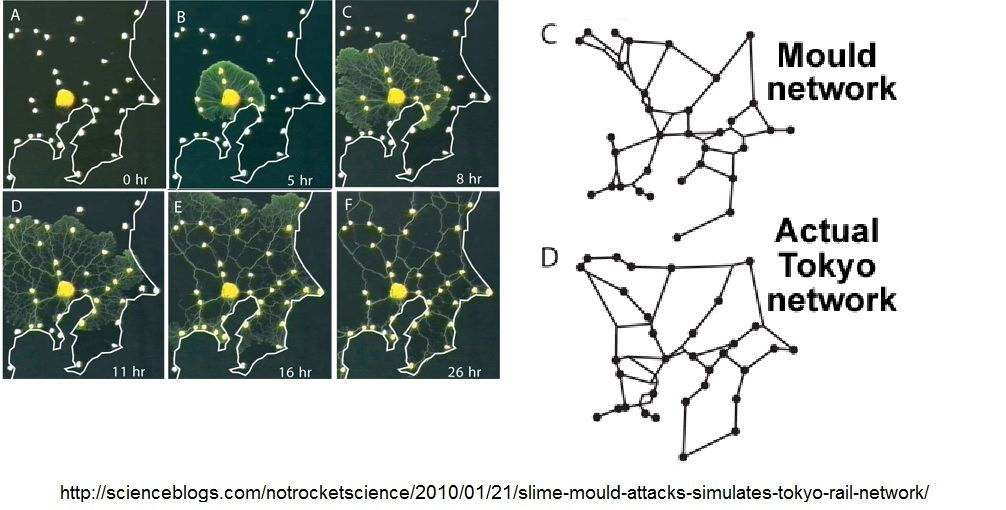

Bridle concludes with a provocation that speaks to the importance of making our human thinking tangible: "Systems of intelligence, computational ability – mycorrhizal networks, slime moulds, and ant colonies to name a few – have always existed in the natural world, but we had to recreate them in our labs and workshops before we were capable of recognizing them elsewhere” (194, emphasis is mine). Bridle's point is that once we made tangible our technological concepts of the world wide web and, later, neural networks, it knocked loose our petrified perceptions of the natural world, seeing forests anew as networks of complexity and interconnection, for instance. This could explain society's delayed acceptance of Suzanne Simard's work, as represented in her recent classic, Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of Forests (2021). For years, the scientific community dismissed her work on the communicative capacities and intelligence of forest systems, but once we started manufacturing analogous models in the computer lab, it's like our perceptual awareness (when turned outward) changed dramatically, as if the act of making adjusted or expanded the mental models through which we perceive and make sense of the world.

And this is the difference, by the way, between machine learning and human learning. While machines are busy collecting data, we have the advantage of fitting data into cognitive models of the world. Learning for our species is less about accumulating facts and more about adjusting mental models to make deeper sense of the world around us. “Just as the advent of networking technologies from the 1960s onwards allowed us to perceive life in new ways, and to open ourselves to new relationships and new modes of being," writes Bridle, "perhaps the advent of intelligent technologies will allow us to perceive the rest of the thinking, acting, and being world in ways that are more interesting, more just, and more broadly mutually beneficial" (83).

On Slime Intelligence

What really excites me about the intersection of technology, nature, and human perception is the reciprocity of it all. Just as technology can transform how we see, make sense of, and relate to nature, the ecological systems of intelligence (out in the world) can also shape and transform how we understand modern technology and its use cases. Bridle shares how in recent years city planners, engineers, and scientists studied slime molds, specifically the species Physarum polycephalum, in order to recreate one of the modern world's more complicated transportation systems: "When researchers placed oat flakes... in the pattern of the cities surrounding Tokyo,... the slime mould quickly reproduced their efforts... Within a few hours it started to hone its web of threads into a highly efficient network for distributing nutrients between distant ‘stations,’ with stronger, more resilient trunk routes connecting central hubs. This wasn’t a simple, join-the-dots exercise either, but a realistic map... requiring the mould to make the same kind of trade-offs that engineers have to implement" (192). Just as technology shapes our perception of nature, the collective intelligence of our natural systems have the potential and power to teach us so much about our models for technology as well. And we should listen.

What this tells us is that biomimicry and AI are two opportunities to reconnect student inquiry to an interconnected system where everyone matters: Where we matter; where technology matters; and where slime molds matter too. With this said, how might acknowledging our entanglement with nature help make "the physics of school" make sense? More specifically, what can nature teach us, not just about transportation systems, but about behavioral health and wellness and about our place of belonging in the cosmos?

David Abram concludes his environmentalist call to awareness, The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in the More-Than-Human World (2017), lamenting our "progressive forgetting of the air" as a human species, which "has been accompanied by a concomitant internalization of human awareness… an isolated intelligence located ‘inside’ the material body [which] can only be understood in relation to the forgetting of the air, to the forgetting of this sensuous but unseen medium that continually flows in and out of the breathing body…" (257). This "unseen medium" is like the unacknowledged water in Aquaman's world – a world where the physics just doesn't seem to be working the way it was promised to play out.

As we respond to the rise of AI, especially in the context of rising rates of depression and anxiety, how do we not see it as the last nail in the coffin of human supremacy but as a reminder or invitation to reconnect, on our common ground of intelligence, with nature? As David Abram puts it, it's about reclaiming our connection with "earthly nature as a densely interconnected organic network–a ‘biospheric web’ wherein each entity draws its specific character from its relations, direct and indirect, to all the others... as an intertwined, and actively intertwining, lattice of mutually dependent phenomena, both sensorial and sentient, of which our own sensing bodies are a part” (Abram 85).

We are a part of something, and if AI can teach us anything, it's not that we matter less; it's that we matter all the more because the world relies on us, on our ingenuity, and on our empathic capacity to connect with the more-than-human system of life, beauty, and becoming.

What if we more intentionally invited students to join the sensuous, living network of belonging and collective intelligence? What if learner-centered pedagogy meant finding their place in this network and taking responsibility for it?

Sources:

- Abrams, Zara. "Kids' Mental Health Is in Crisis. Here's What Psychologists Are Doing to Help."American Psychological Association's 2023 Trends Report, 1 January 2023. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2023/01/trends-improving-youth-mental-health.

- Levasseur, Aran. "The Biggest Problem For Kids Today Isn't Stress, It's Lack of Purpose." Ed Post, 28 October 2019. https://www.edpost.com/stories/the-biggest-problem-for-kids-today-isnt-stress-its-lack-of-purpose.

- Plato. Phaedrus from The Collected Dialogues of Plato. Trans. R. Hackworth (1952). Eds. Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns. Princeton University Press, 2009.

- Challenger, Melanie. How To Be Animal: A New History of What It Means to Be Human. Penguin Books, 2021.

- Dehaene, Stanislas. How We Learn: Why Brains Learn Better Than Any Machine... For Now. Penguin Books, 2020.

- Bridle, James. Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for Planetary Intelligence. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022.

- Abram, David. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in the More-Than-Human World. Vintage Books, 2017.

- Turing, Alan M. "Computing Machinery and Intelligence." Mind, 49: 433-460, 1950.

- Yonck, Richard. Future Minds: The Rise of Intelligence from the Big Bang to the End of the Universe. Arcade, 2020.

- Marcus, Gary and Ernest Davis. Rebooting AI: Building Artificial Intelligence We Can Trust. Vintage, 2020.

- Russell, Stuart. Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control. Penguin Books, 2020.

- Levesque, Hector. Common Sense, The Turing Test, and the Quest for Real AI. The MIT Press, 2017.

- Martin, Leanne, Mathew P. White, Anne Hunt, Miles Richardson, Sabine Pahl, and Jim Burt. "Nature contact, nature connectedness and associations with health, wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviours." Journal of Environmental Psychology, 68, 101389, 2020. https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk/

bitstream/handle/10026.1/15691/Martin, White, Hunt, Richardson, Pahl & Burt(2020).pdf;jsessionid=EE4E6D6B734958A2E495AEA6728099AE?sequence=1. - Passmore, Holli-Anne and Ashley N. Krause. "The Beyond-Human Natural World: Providing Meaning and Making Meaning." Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 20(12), 6170, 2023. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/20/12/6170?type=check_update&version=1.

- Jimenez, Marcia P., Nicole V. DeVille, Elise G. Elliott, Jessica E. Schiff, Grete E. Wilt, Jaime E. Hart, and Peter James. "Associations between Nature Exposure and Health: A Review of the Evidence." Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 18(9): 4790, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8125471/.

- Simard, Suzanne. Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest. Vintage, 2022.

Comments