We are in the midst of semester exams, and I’m finishing up my grading for the semester. I’m in the unenviable position of being an English teacher whose exam — a piece of writing, of course — comes on the last day. So, I’m biding my time, getting everything in order so that when those exams hit my inbox next week, I can speed right through them.

In the meantime, I’m looking at this grade book, and I’m starting to get a little bit worried. Over the past two years, I’ve made some changes to the way that I determine grades in my class, and those changes seem to be having the same result: the grades in my classes are really high. Like, most of my students are now earning an A- or even better. When these grades post, what will people think? What will the administration think? Will I be told my grades are too high? Have I watered down the curriculum?

First, let’s get something straight: worrying too much about what other people think is a surefire way to (a) drive you mad and (b) ensure that you’ll never be fully yourself. Second, no, I have not “watered down the curriculum.”

What I have done, inspired by my department chair, Alexis, is think about grading in new ways. A few years ago, Alexis started toying with what she called “Revision-Based Assessment.” She brought me onboard last year for a test class, and now I’m fully in, using these ideas in all of my classes. I’m hoping to write about this in a series of posts here, so I just want to start by giving you the basic philosophy as I’ve kind of developed it for myself.

The philosophy begins with three basic premises/principles:

- Nothing is one-and-done.

- Publishable is the goal.

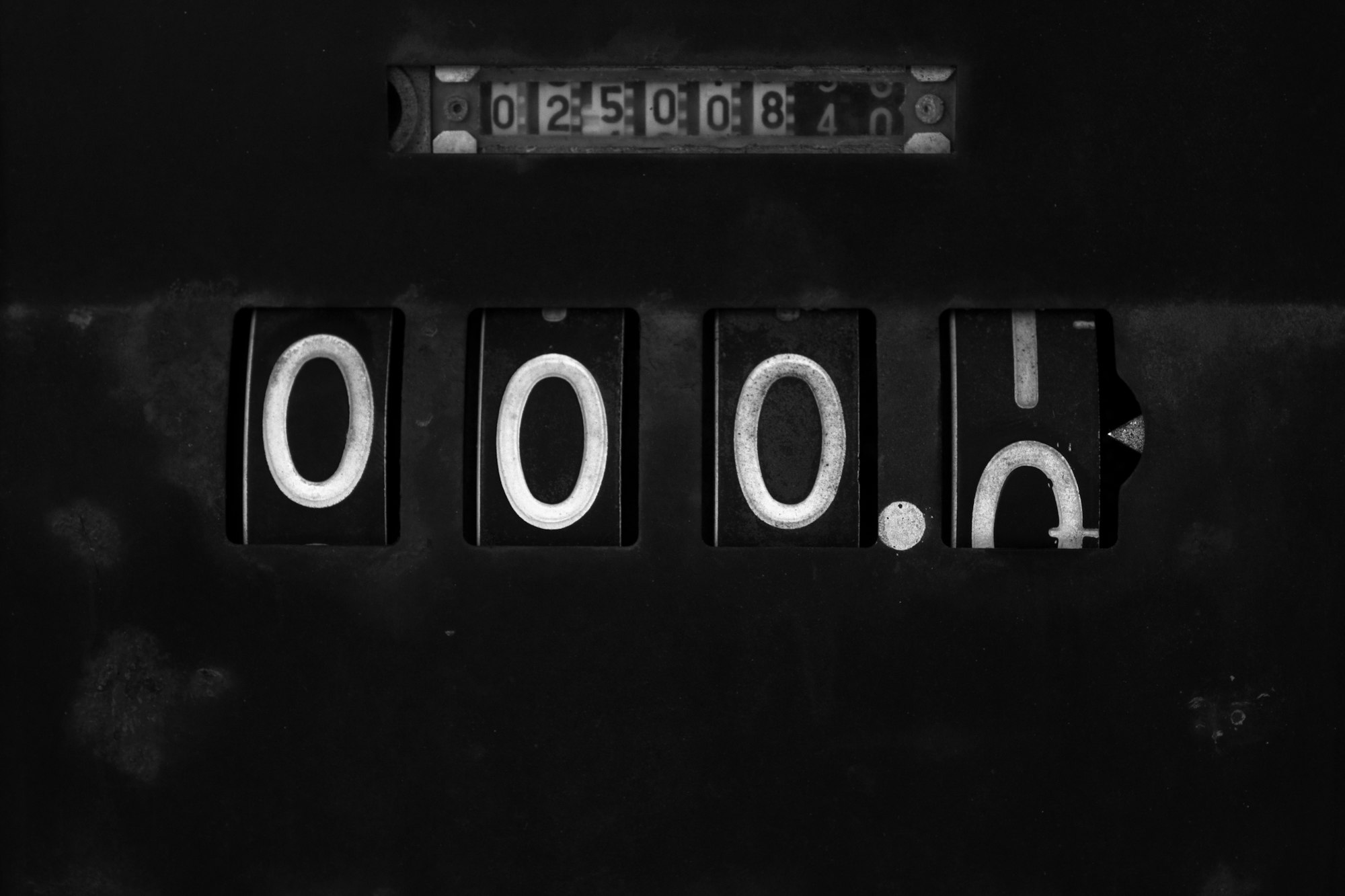

- We start from zero.

My hope is that these principles encourage a growth mindset (the clouds part and angel-song reverberates through the cosmos). I also hope they help students to understand the value of iteration; in writing, this means keeping at it until the piece is what you really want it to be.

For today, let’s look at each of these principles and what they mean.

1. Nothing is one-and-done.

A foundational text in many writing classes is Anne Lamott’s “Shitty First Drafts.” If you haven’t read it, go read it. It’s a good time. The whole book, Bird by Bird, is great. Lamott’s premise here is this: the first draft is going to be shitty. Get through it; then, start working on the second draft. That’s where things get good.

Yet, most of our assignments in schools are setup around a one-and-done model. Yes, we encourage students to participate in the writing process. We may even have them turn in “rough drafts” or do rounds of peer review. This is good, but eventually the student turns the assignment in and receives a grade for it. Sometimes, we will allow the student to revise the assignment based on our feedback, but the students new grade is typically some percentage of the old grade: a you-can-earn-back-half-your-points kind of a thing.

But this isn’t how writing really works in the world, nor is it, in my view, the way to learn how to write.

Principle One: Nothing is one-and-done.

Therefore, revisions are encouraged, and you will earn a brand new grade based on that revision. It doesn’t matter where the assignment started, what matters is where you are right now. If you would like to keep working on this, you deserve full credit for the fruits of those efforts.

Thus, in my classes, you can continue to improve a piece of writing until the end of the semester. Last year, I had one student produce about 15 drafts of her summer reading assignment (a book review). She really wanted to nail it and get it right. Eventually, she did! As a teacher of writing, what could be a greater success?

If you don’t like the result, do it again!

2. Publishable is the goal.

I once worked at a school where grades all had to be on a 100-point scale. When I looked at an essay, I had to think to myself: “What is the difference between a 95 and a 94? A 94 and a 93? Etc.” Even with a good rubric, I found it really hard to make these decisions. The level of specificity was just too much.

For most of my career, I’ve worked in an A–F, letter-based, system. This is an improvement over the 100-point scale, in my view, because the measurements aren’t so fine.

The problem with grading systems like these, however, is that they don’t necessarily communicate what we want them to communicate. When I ask students what an A means, they have different answers. Some tell me it means they put in a lot of effort; others tell me it means they wrote good papers. Many students, of course, believe they should earn As for showing up.

If we’re going to map a letter or number system, a grade, on to a writing curriculum, then we have to think about what the goal of writing is. When I think about writing, the goal really is too communicate, to express, to be heard. To fully express our thoughts, to make our minds known, we’ve got to write something that is worthy of publication.

Principle Two: Publishable is the goal.

In our classes, we have adopted a much simpler system for marking papers. We have three categories:

- Publishable. This essay is excellent, (nearly) flawless. It is worthy of publication. (In one of my classes, we’ll even publish it, but more on that another time.)

- Revisable. This piece is headed in a good direction, but we’ve got some things to work on. Act on the feedback and submit another draft.

- Redo. This effort does not meet the basic requirements of the assignment. You might need to start over from scratch.

When I look at a paper, that’s what I’m thinking as I read it: “Is this worthy of publication?” If not, then it’s probably revisable. Cool! Mark the most important items that the student needs to work on and encourage them to do so!

When they receive the paper, students get to make a decision. If they don’t like the result, they can do it again.

3. We start from zero.

One of my least favorite questions from students is this: “Why did I lose points on this?” I sometimes look at them blankly as I hold their essay in my hand. I’ve commented on this thing quite heavily, yet somehow the answer is opaque to the student. Patiently (usually), I walk them through the feedback, the marks on the paper, the marks on the rubric.

Never, however, have I had a student ask me the inverse of this question: “Why did I earn points on this?”

Most (all?) of my students tend to show up believing that their grade is a thing to lose. They believe they’ve come in with the A+ or the 100. For these students, the assignments are a kind of game they play where they try not to lose points. Our systems are setup to encourage this, but it’s working against the holy grail of education: growth mindset.

A few years ago, Jared and Nick inspired me to think the other way around. They were working on gamifying their classes, and I did the same. I taught a unit in my American Literature course where students participated in a roleplaying game. They were swept back into 17th-century Boston and had to work with Hester Prynne to free themselves from their temporal prison. It was super-nerdy! Students earned experience points and skill points as they tried things in the game and gained new skills/proficiencies. Everyone started at zero and then worked their way up.

Isn’t this the way that education really works? At its most basic level, don’t we start not knowing how to do things, and then we have to put in some effort to learn how to do them?

If you asked me how to sew together a pair pants right now, I’d have no clue where to even begin. If you were teaching me how to do this, then you might say that my knowledge and skills were at an F-level: I’m currently a failure at tailoring pants. However, as I work through your awesome pants-making class, I’m going to get better. As I learn how to design a pattern and how to cut the fabric, as I learn how to measure the customer and work a sewing machine, I’m gaining in proficiency. I’m moving from zero knowledge to some knowledge. I’m not losing points. Quite the opposite! I’m gaining!

Principle Three: We start from zero.

In my classes, students start with nothing and have to build their way up to the grade that they deserve. How do they do that? By revising their writing until it’s “publishable.”

Put it all together.

When we take these principles and put them together, here’s what we end up with: a writing course where students are encouraged to act on feedback to improve their writing skills.

There are some other byproducts of this:

- I have conversations with students about growth mindset, encouraging the development of such a thing.

- I see students, through the process of revision, produce really excellent writing.

- Students earn higher grades because they produce really excellent writing; thus, we map the grade to the product.

- We focus on the skills and the learning, not just on the grade.

I’ve tried just about every grading system under the sun: traditional systems, standards-based, no grades, etc. But starting with these three key principles, I really think I’m hitting my stride.

Thoughts?

In the coming weeks (months? years?), I’ll continue to unpack these three principles. If you have questions or comments, feel free to express them below or send me a tweet!

Comments