How might we provide feedback that is powerful, purposeful, and motivating as opposed to feedback that demotivates or disempowers the student because it lacks purpose or clarity?

Motivation is to learning as oxygen is to breathing.

Not too long ago, a teacher approached me to let me know that she planned to give a certain student an 'F' on their scheduled two-week grade report - not because it captured the student's level of achievement or learning progress but because she thought it would motivate the student to turn in some missing assignments. Let's just say I didn't see it like that, which led to a productive conversation about the relationship between grading and student motivation.

I remember when I picked up Margery B. Ginsberg's book, Excited to Learn: Motivation and Culturally Responsive Teaching, and the title of this section's heading was printed top and center on the back cover: Motivation is to learning as oxygen is to breathing. It caught my attention because, as I already knew, if a student isn't motivated, learning is like trying breath while suffering from COVID - the oxygen just doesn't seem to be getting to the blood stream, making the experience oppressive and exhausting, thereby depleting the student of any and all vigor.

Motivation brings learning to life. No doubt. But how do we spark and sustain it?

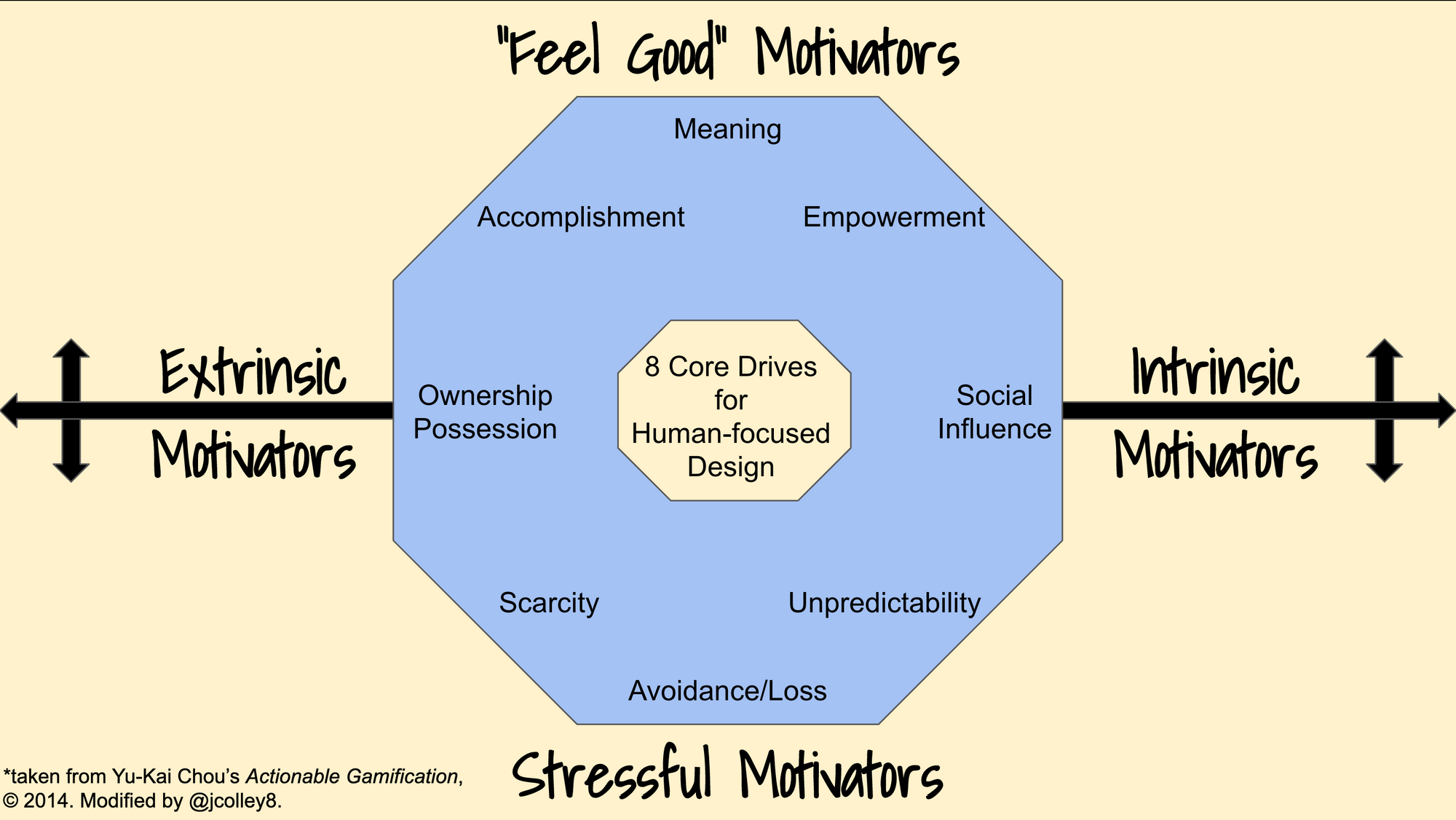

In Making Classrooms Better: 50 Practical Applications of Mind, Brain, and Education Science, Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa adds an important insight to Ginsberg's mantra. She connects it to what we're exploring in this post, namely feedback: "Two main pairs of motivators in psychology are positive-negative and intrinsic-extrinsic," and of course, she affirms the belief that "intrinsic motivators work best," especially in the context of education. However, she pushes the thought further stating, "[I]t is incumbent on external forces, often the teacher, to cultivate this belief in students through the feedback process, [meaning] feedback, then, takes on a new twist and grows beyond to being an instructional tool that hopefully catalyzes motivation to improve." Feedback is a tool that helps us move from external to internal forces for deepening and expanding a student's learning. In other words, feedback (when done well) can serve as the tool that bridges extrinsic-negative forms of motivation to ones that are more intrinsic-positive in nature. As educators, if we do it right, we can cultivate and nurture intrinsic desire through the feedback process!

In the context of Game Design, Yu-Kai Chou makes the case that, to create long-lasting user engagement with a game, the designer must rely on extrinsic (and sometimes stressful) motivators to create the call to urgency for the game user, but if the the game design doesn't transition the user's experience to more positive, intrinsic sources to motivate game play, the user will eventually disengage.

A game might create urgency to jumpstart the user's engagement, simply by relying on factors related to the bottom-left part of the above image. In Fortnite, for instance, the player parachutes down onto the island, and they better act quickly because weapons are scarce and threats are all around you. However, if the game doesn't bridge the user's experience to the "golden corner" (the top-right part in the above image), eventually the player loses interest. Fortnite does this well by creating community and letting players express their creativity, for instance.

Engagement is sustained through a sense of purpose and empowerment, not by way of the threat of an 'F' (if we return to the story of the teacher I mentioned). If it were just about scarcity (only a few can truly succeed) or avoidance of loss (don't screw up or I'll take away points), sooner or later the motivational oxygen stops making its way to the learner's bloodstream, and eventually it runs out. And when the student flatlines, an 'F' will make a difference on the their transcript, for sure, but it won't function as a motivational defibrillator.

Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa's comment from Making Classrooms Better presents a similar picture: learning (in the context of schooling) may begin with external factors or motivators (grades, expectations for accomplishment, a teacher's call to action, synchronous schedules, etc.), but feedback is an invaluable tool (and not the only one; I think of student choice and voice, for instance) that helps us pave the path towards a better student experience - one that feels good and is driven by intrinsic desire. What won't serve as that bridge, as already stated, is the threat of an 'F' - especially for the student who already demonstrates signs of disengagement.

The different functions of feedback

It would be remiss if I continued to talk feedback without acknowledging the work of John Hattie and his Visible Learning team. In Visible Learning and the Science of How We Learn, I deciphered at least 5 functions of feedback (and the italics below are my added insights):

- Feedback affirms and specifically describes what the student did well (this kind of feedback occurs at every stage of a learner's journey from being a novice to becoming advanced)

- Feedback can focus on the task at hand and whether it is being done correctly or incorrectly - what Hattie calls "correct and direct" (this kind of feedback is useful for the student who is a novice or is emergent in relation to a given skill, standard, or competency)

- Feedback can focus on pointing out the process that the student used to complete the task (this kind of feedback is useful for the student who is moving from emergent to proficient in relation to a given skill, standard, or competency)

- Feedback can focus on self-regulation by using questioning to further the student's self-evaluation of skills and to monitor their own actions (this kind of feedback is useful for the proficient student who is moving towards advanced in relation to a given skill, standard, or competency)

- Feedback can focus on the self - on the learner and not the learning, per se (this kind of feedback is useful for developing a conversation, less about academic achievement, and more about mindsets and work habits)

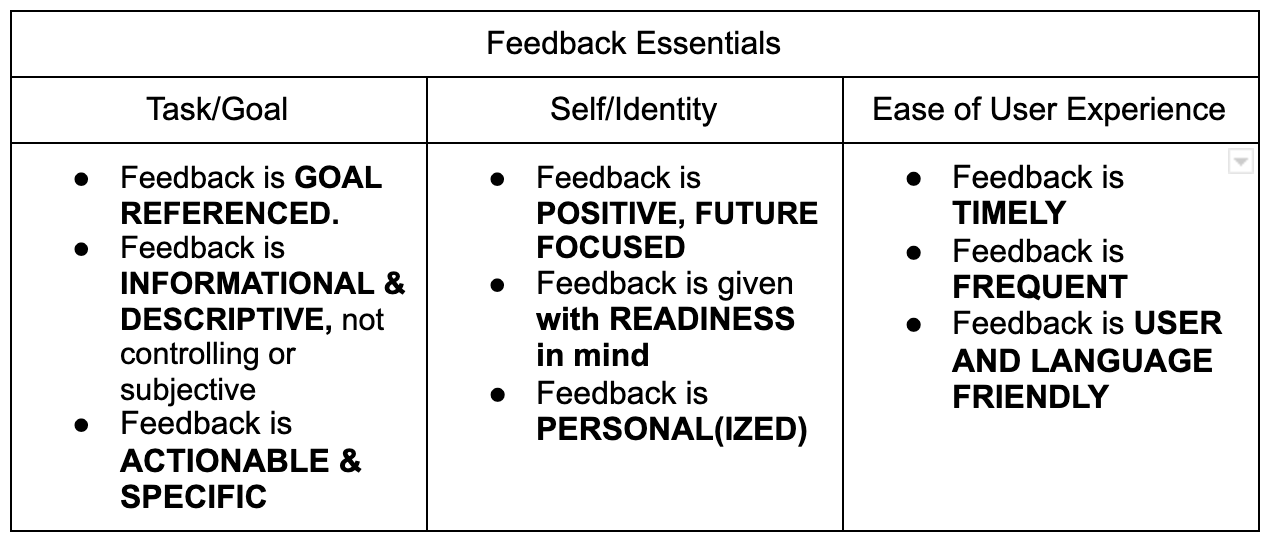

Inspired by Hattie's work (as well as by some of the other authors referenced in this post), I developed a 3-part synthesis about what constitutes positive, motivational feedback: (1) It must be actionable, goal-oriented, and forward looking - focusing less on mistakes of the past and more on the goals that can be reached in the future; (2) It has to support a student's identity and sense of self, meaning it's rooted in a relationship of care and trust while also mindful of a student's readiness to receive it; and (3) A teacher must always consider the user's experience in terms of timeliness, volume, and frequency as well as whether the language deployed is suitable for the student's stage of development.

An important thing to keep in mind is that each of these pillars are not separate categories; in fact, each one reinforces and supports the other in order to prop up the primary purpose of the feedback process: to intrinsically motivate students to become what Zaretta Hammond calls independent learners (see Chapter One of her book, Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain, Corwin 2015).

Feedback that focuses on the task or goal

To risk stating the obvious, feedback has to be goal-oriented and "based upon agreed upon standards and criteria for success" (Ginsberg Excited to Learn: Motivation and Culturally Responsive Teaching, Corwin 2015). The more I examine both my feedback practice in previous years as well as that of other instructors, it becomes clear that we do need this reminder. Too often feedback focuses on the mistakes of the past and does so without a clearly stated standard or learning outcome for the student to visualize and work toward. "Think of learning how to juggle," writes Emily Rinkema and Stan Williams. "You take three balls and throw them into the air. You catch one, but the others fall. Immediate feedback - it didn't work... How did you know you failed? Because you know what it looks like when someone succeeds at juggling. You can see the target and you can compare yourself to that target right now" (The Standards-Based Classroom: Making Learning the Goal, Corwin 2019).

To provide a clear picture of what it looks like to progress and succeed, the language one employs needs to be descriptive and informational rather than subjective and consequently controlling. Zaretta Hammond describes it as "instructive feedback that helped [the student] make specific adjustments rather than evaluative feedback that just told [the learner] whether what you did was good or bad but offered no information to get better" (Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain).

Pointing out the path towards success is about so much more than guiding the student forward; it's about an "explicit holding of high standards." As Zaretta Hammond says, "This helps the student understand that his or her mistakes are not necessarily a sign of low capability but rather a sign of the high demands of the education program." This is where a goal-oriented focus supports the second element of effective feedback. As Claude Steele argues in Whistling Vivaldi and Other Clues to How Stereotypes Affect Us, it's important we frame feedback as "a narrative of intelligence [that is] more expandable. Such a narrative would frame academic frustration as a fixable problem rather than as an unfixable limitation." Forward looking feedback that harps less on the past has the power to diminish what Claude Steele calls "Stereotype Threat," which is one of the many barriers that teachers in partnership with their students must overcome to cultivate and empower independent learners in a culturally diverse environment.

Feedback that focuses on the Self & Identity

As teachers we have a responsibility to care for our students' identities, and if we don't, feedback will have no lasting effect. Forward looking feedback, therefore, has to be positive, "placing emphasis on improvements and progress rather than on deficiencies and mistakes” (Ginsberg Excited to Learn: Motivation and Culturally Responsive Teaching).

Authors, Tom Schimmer, Garnet Hillman, and Mandy Stalets, ask us as teachers to consider the fact that students are really concerned about two pathways when navigating the school day: one is a Growth Pathway and the other is a Well-being Pathway (Standards-Based Learning in Action: Moving from Theory to Practice, Solution Tree 2018). If we focus on the first while neglecting the latter, the feedback we give will have no impact, and research in brain science confirms this. "To survive the brain depends on getting regular feedback from the environment," writes Zaretta Hammond, "so that it can adjust its strategy in its efforts to minimize threats and maximize well-being" (Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain). When students receive messaging that makes them feel unsafe (or even fail to receive messaging that they are safe and they belong), "The body starts to produce stress hormones that make learning nearly impossible" (Hammond).

What this means is that teacher-student "relationships are not just emotional; they have a physical component," and without establishing a relational foundation of trust and belonging, students will never be emotionally and physically ready to receive the feedback we'd like to give. Zaretta Hammond argues that, "Contrary to what we may think, simply giving feedback doesn’t initiate change. It has to be accepted as valid and actionable by the learner. He then has to commit to using that information to do something different. For dependent learners this can be scary. Part of our role as an ally is to offer emotional support as well as tools.”

For this reason, feedback also has to be personalized. For years, I gave feedback on student writing, relying on a stock of ready-made comments to make the process less time consuming. I'm not advising against such a strategy, but if one stops there, it's a one-way conversation where the vulnerable learner most likely won't feel heard. “We have to engage our students’ willingness to act on our feedback. By looking closely at their work to understand what they get and identify where they need help, we are listening to our students. Our feedback can communicate to them that we have heard them, and they will be more likely to trust us enough to follow our advice for that sometimes difficult next step” (Hammond). Making it personal also means speaking to them when they need it and not speaking at them when we finally get around to grading a batch of assignments. In this way, feedback that cares for the self also considers the receiver's experience from their perspective.

Feedback that accommodates the user's ease of experience

If we want to speak to the student, we have to think about the impact, timing, and frequency of our practice. It goes without saying that it needs to be timely, but that doesn't always mean immediate. It can be immediate - such as a conversation in class - but a proper guiding principle is to give students feedback "at a time when they're most able to use it" (Schimmer, Hillman, & Stalets, Standards-Based Learning in Action). If a student is preparing for a summative assessment, for instance, conferencing with the learner about their formative practice before the summative experience is imperative. They don't need grades on formative assessments; they need timely feedback to position them for success on the upcoming summative. This relates to another issue (that deserves its own post) having to do with time being the variable and not the constant when it comes to assessment in general; not every student is ready to take a summative assessment at the same time.

Feedback needs to be more frequent than grade reporting, but not excessive such that it overwhelms: “A good rule of thumb is to provide feedback when improvement is most possible” (Ginsberg Excited to Learn: Motivation and Culturally Responsive Teaching). That means knowing your students individually and being able to respond accordingly.

Lastly, It needs to be user-friendly in terms of the language and expressions we employ. Students don't need jargon, but they also have little use for vague statements of affirmation like "good job" or "nice work." As already stated, what they really want are specific, descriptive, actionable suggestions that they can respond to immediately.

Closing: Making Feedback More Manageable

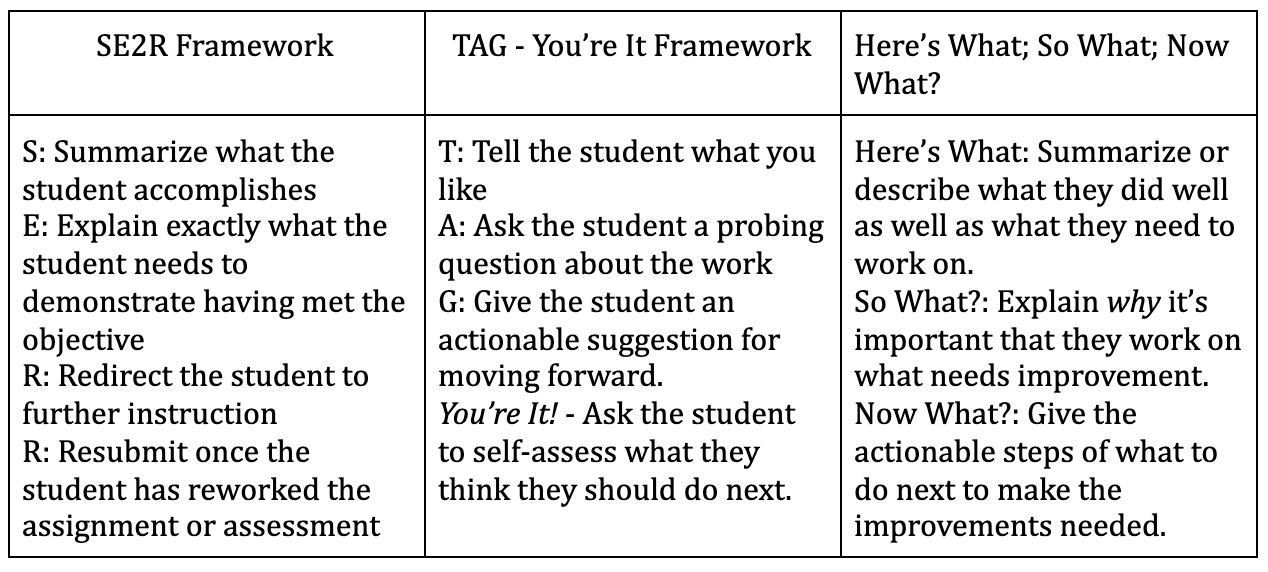

Keep in mind that feedback can take many forms: conversations, written comments (narrative & descriptive), digital feedback (Screencastify; Kaizena; etc.), peer feedback, exit tickets, and well-written rubrics that make self-evaluation possible. Consider previously developed feedback frameworks to shape and organize your communication to the student:

Make feedback more real-time and conversational, when appropriate, by making time for doing things in class. This is where the flipped classroom got something right. When it comes to Bloom’s taxonomy or Webb’s Depth of Knowledge levels, students need to be doing the more cognitively demanding work in class so we can coach, redirect, question, and encourage students, such that feedback becomes a real-time, formative experience. And remember, “we do not need to collect everything and score everything and comment on everything. Instead, we need to design practice opportunities and a class structure that allow us to see the learning and provide feedback (a quick comment, a redirection, small group instruction, targeted practice). That means that class should be the time when students are doing and we are watching them do… It means rethinking how we use our time so that students access our content by being more than receptacles to our delivery” (Rinkema and Williams, The Standards-Based Classroom: Making Learning the Goal, Corwin 2019).

References and recommended reading:

Chou, Yu-Kai. Actionable Gamification: Beyond Points, Badges, and Leaderboards. CreateSpace Independent Publishing, 2015.

Ginsberg, Margery B. Excited to Learn: Motivation and Culturally Responsive Teaching. Corwin, 2015.

Hammond, Zaretta. Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students. Corwin, 2015.

Hattie, John and Gregory Yates. Visible Learning and the Science of How We Learn. Routledge, 2014.

Rinkema, Emily. The Standards-Based Classroom: Making Learning the Goal, Corwin, 2019.

Schimmer, Tom, Garnet Hillman, and Mandy Stalets. Standards-Based Learning in Action: Moving from Theory to Practice. Solution Tree, 2018.

Steele, Claude M. Whistling Vivaldi and Other Clues to How Stereotypes Affect Us. W. W. Norton, 2010.

Tokuhama-Espinosa, Tracey. Making Classrooms Better: 50 Practical Applications of Mind, Brain, and Education Science. W. W. Norton, 2014.

Comments