Instead of asking, what can machines do better than humans? And what can humans do better than machines? What if we asked, what do humans need to learn and do to thrive in an age of intelligent technology?

What Remains Human in the Age of Intelligent Machines? Authentic vs. Artificial Intelligence

In some recent posts, I referenced Plato's Phaedrus in the context of AI to remind readers of two concerns he (and his protagonist, Socrates) had about the new form of technology known as writing:

- Writing would "implant forgetfulness" because humans would "cease to exercise memory." Technology, in other words, would make us less reliant on exercising and honing our cognitive capacities. (more on that here)

- And, "once a thing is put into writing, the composition, whatever it may be, [could drift] all over the place," and what if the information that's adrift is bad (or misunderstood) information? (more on that here)

Familiar concerns, if you've been listening to current conversations about AI in the age of (dis)information.

"Plato was teaching," writes David Abram, "precisely at the moment when the new technology of reading and writing was shedding its specialized 'craft' status and finally spreading, by means of the Greek curriculum, into the the culture at large" (108). Plato, more so than anyone else, recognized the profound effects that this new technology would have on human culture, on how we live, work, and learn, as well as on on our collective understanding of what it means to be human.

And Plato was right on some level: Writing changed us. Or better yet, it revealed or brought to the surface aspects of our humanity we may have not been attuned to otherwise, and AI will do the same in this century.

Teachers today, like Plato, are witnessing the spread of this new technology, both in our modern curricula and in our daily experiences, and already it is profoundly changing things. The teachers I talk to feel a similar discomfort when witnessing the uncanny powers of generative artificial intelligence, a technology that is no longer a "craft" reserved for engineers in computer science labs: we all can access and harness its power.

Much of the discussion around artificial intelligence, like writing, is just as much about redefining what it means to be human and identifying that remainder that sets us apart from these new technologies. Plato wondered what it would mean to be human if memory and information are extracted, outsourced, and disseminated by technologies that no longer rely on embodied, human cognition as the means for doing so, and similarly, teachers (and other professionals, for that matter) are wondering what remains for them - as well as what will remain for their students in an age of increasingly intelligent machines.

I'd like to make the case that there's good news ahead.

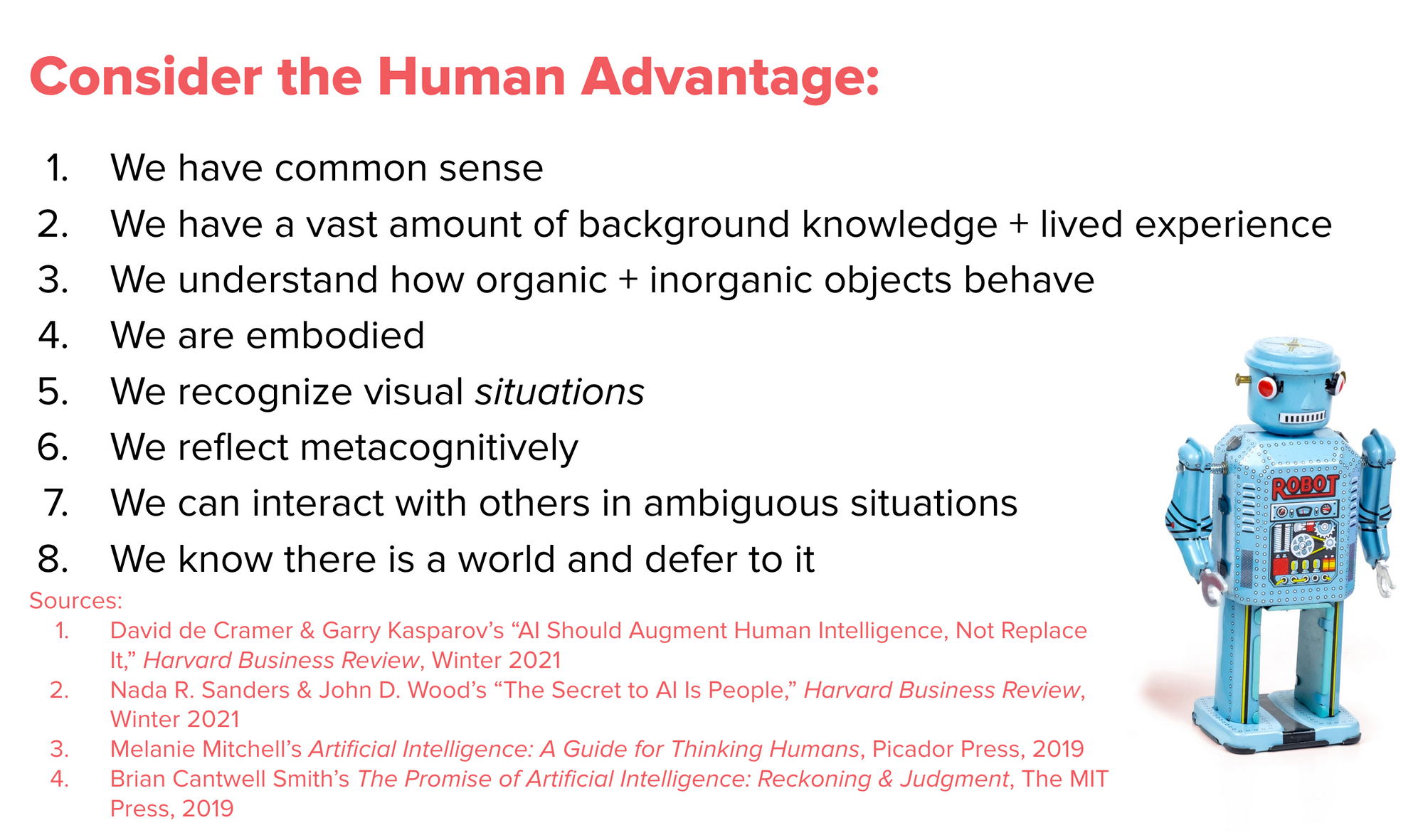

The Human Advantage

It's important to emphasize that “the question of whether AI will replace workers assumes that AI and humans have the same qualities and abilities–but, in reality, they don’t. AI-based machines are fast, more accurate, and consistently rational, but they aren’t intuitive, emotional, or culturally [responsive]” (de Cramer and Kasparov 97-98, 2021). Replacement is not the right relational concept, in other words; after all, writing did not replace our memories. Oral histories, for instance, are still one of the greatest resources for research historians.

The reality is that while machines learn to do certain tasks whose output is “more precise and faster,” human skills like “creativity, care, intuition, adaptability, and innovation are increasingly imperative to human success” (Sanders and Wood 129, 2021). What all this means is, not only is there a human remainder, there's a clear human advantage:

Rest assured, there are lots of tasks to be done by humans in the age of intelligent machines–tasks that require one to handle complex communication, to apply information strategically, to generate ideation, to read information discernibly, and to engage in complicated sensori-motor work (Brynjolfsson & McAfee 201-202, 2014). With this in mind, we should invest in this human advantage by focusing less on substituting human cognition and more on augmenting it, which can happen if we learn how to "work well with machines" - something I think Plato had doubts about.

Working Well With Machines... and People... and Nature: The Necessity of Collective Intelligence

The ability to work well with machines will be an integral competency in the age of AI, what one might “call fusion skills–those that enable [people] to work effectively at the human-machine interface” (Wilson and Daughtery 92, 2021). It is an ability to know when and how to combine the “technical acuity” of machines with human strategic thinking (Brynjolfsson & McAfee 189-190, 2014), but it is also the ability to exercise a knowledgeable understanding of what it means to be "AI literate" (something I addressed in my previous post). I think this was the real source of Plato's concern: instead of augmenting human performance and experience, writing would make us vulnerable to forgetfulness, misinformation, and misunderstanding.

But was he right? What if the capacity of these machines could potentially augment or even modify the human advantage? What if we focused less on substitution of jobs and people and directed our attention to augmenting and modifying tasks and processes? (And yes, I am reappropriating the SAMR framework here...)

From this perspective, the outcomes we achieve on our own will pale in comparison to outcomes we can achieve through augmented and modified means made possible by partnerships of collective and collaborative intelligence, partnerships that may be with machines, other humans, but also with the systems of the natural world. Like one author predicts, “In the near future there may be classes of problems so deep that they require hundreds of different species of minds to solve” (Kelly 47, 2016). When discussing the collective intelligence of human groups, one educational expert writes, “It has become clear that a group’s ‘intelligence’ does not come solely from the intelligence of its members. Indeed, one advantage of a team is that gaps in each team member’s knowledge and skill can be covered by other team members who happen to be more competent in peers’ gap areas” (Lesgold 53-54, 2019). In an era when complex problems emerge rapidly, no single expert will be able to find the solution, but experts who work well with machines and other people could potentially replace experts who avoid doing so.

Perhaps this is what sets our moment apart from Plato's experience - namely, this time we don't have a choice. For instance, one philosopher of education claims that already the complexity of the world's problems has far exceeded the capabilities of individual humans, meaning that our planet’s educational crisis is actually a crisis of competency (Stein 18, 2019). This demands us to come together collaboratively–machines, people, and things–to discover and realize some viable form of collective, planetary intelligence (Bridle, 2022).

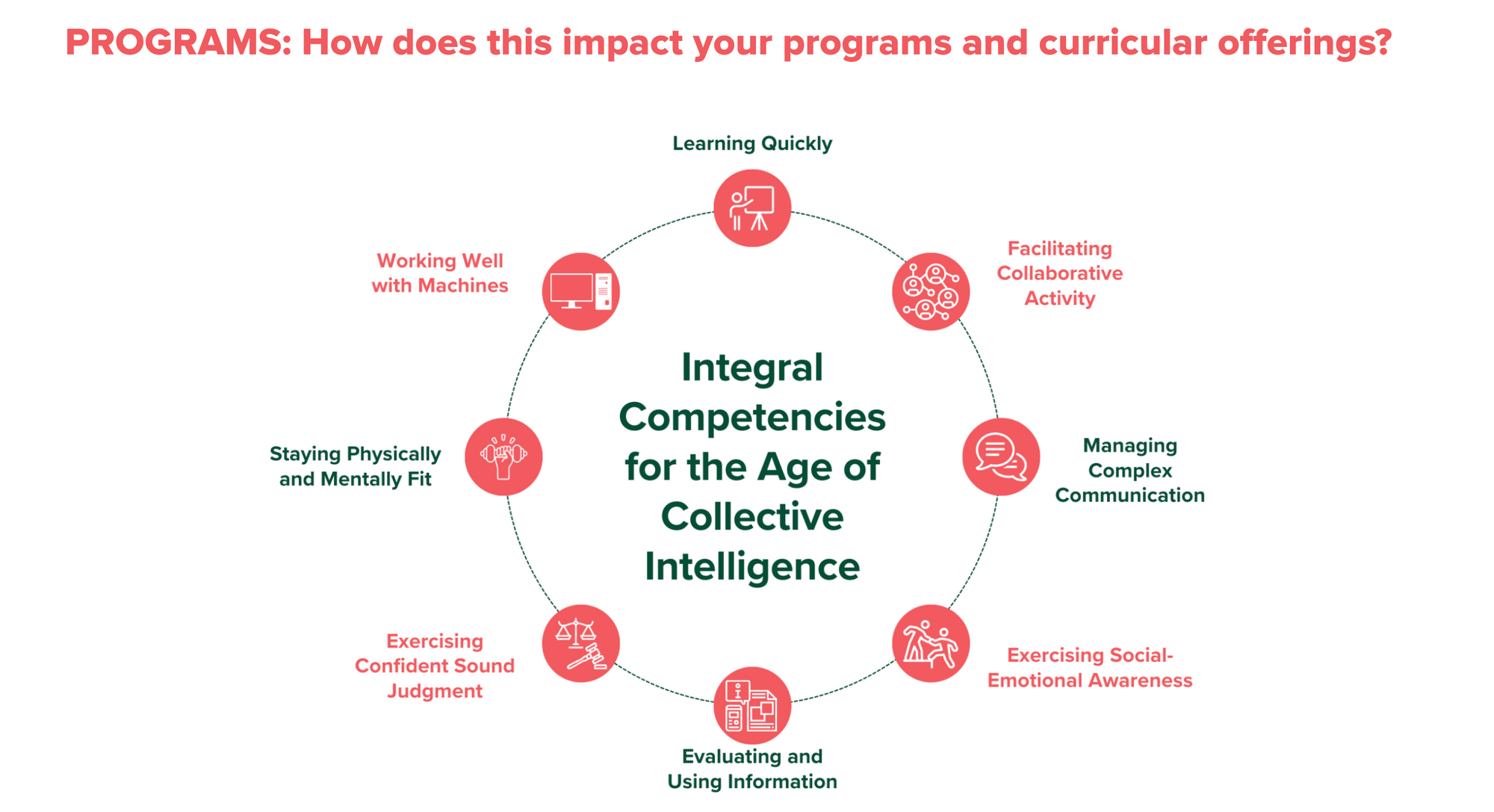

But what are the integral competencies that will empower both educators and students to thrive in the age of intelligent machines? How do we maximize the impact of our human advantage?

Integral Competencies in the Age of Collective Intelligence

In the book Running With Robots: The American High School’s Third Century, the authors ask us to think about the shift from content fluency to content literacies, claiming “What students need from school today is not so much content fluency but, rather, omnidisciplinary content literacy, coupled with process fluency” (Toppo and Tracy 15, 2021). In a pre-AI era that prioritized specific content fluencies, workers and learners alike “needed to have deep knowledge of a narrow area. Today, deep analytical content can come from AI…[whereas humans] need to be able to synthesize information, which means collaborating across functions and working in cross-functional teams” (Sanders and Wood 130, 2021). That requires a certain level of omnidisciplinary literacy. We need to prepare learners not only to have a depth of knowledge but a range of skills and literacies that enable them to develop the following core competencies necessary for the age of collective intelligence:

- Ability to Learn Quickly: Much like we learned when examining the move from 1st to 2nd Wave AI (from a reliance on human programming to an emphasis on machine learning) individuals who only have expertise in a very narrow area will be, at some point, under threat of replacement and obsolescence. The age of AI will not be kind to “brittle” experts and will demand, from all of us, the regenerative capacity to reinvent oneself. I've emphasized how automation will more likely take over tasks and processes, and not necessarily replace jobs and people, but there will be disruption, and many workers will be displaced and required to learn new skills in new areas. This means it’s absolutely necessary to be able “to quickly retool for new roles if current roles disappear” (Lesgold 41, 2019).

- Ability to Facilitate Collaborative Activity: In the age of collective intelligence, the ability to connect with others, facilitate collaborative activity, and navigate group dynamics will be highly valued. When complexity emerges quickly, “the substitute for having an expert… will likely be a team of people with varying expertises who work together to solve problems that require merging their different competencies… The new model will be just-in-time assembly of a team who, working together, can address emergent problems” (Lesgold 18, 2019). This means that schools must do more than just assign “group work”: students need to build the capacity to do complex, multi-staged project-based work with teams of diverse people with varied levels of knowledge and ability.

- Ability to Manage Complex Communication: In order to facilitate collaborative work, we need learners to master the art of complex communication in diverse environments where there are multiple perspectives with various norms and different lived experiences. This means students need significant practice communicating their ideas to people who think differently and to engage with others who possess different knowledge and different cultural identities. Computer programs do not always “read” the nonverbal cues; they don’t really “understand” jokes, sarcasm, and syntactically incorrect statements that a majority of humans can easily decipher. Good communicators and listeners will be necessary in the future.

- Ability to Exercise Social-Emotional Awareness: Both successful collaboration and complex communication require exceptional social-emotional skills as well. “[S]everal things [have] to happen if collaborations… are to work effectively. These include ensuring that all group members have a chance to have their ideas heard, assuring that each member’s contribution is truly understood by the entire team, building on each other’s contributions, considering alternative viewpoints,... and signaling respect and value of each other” (Lesgold 20, 2019). Machines can automate analytical tasks much more rapidly and effectively but they lack the ability to replicate and perform certain social-emotional competencies (Lesgold 44, 2019). There will be a demand for workers who others enjoy being around and would want to work with, especially in the age of increased automation.

- Ability to Evaluate and Strategically Use Information: In a world where information flows at breakneck speeds from unknown sources, much is asked of us as the executive decision-makers. It’s not enough to just evaluate the information; we need to know what to do with it, especially in the context of accelerated automation. Not only do we evaluate available information, we also use it to understand a situation, to determine whether we need more (or different) information, and to decide what to do next. These are strategic roles still to be played by humans in the age of intelligent technology (Lesgold 51, 2019). Students, for instance, will need to evaluate different sources and types of information, especially ones with conflicting perspectives. By doing so, we build resilience, capacity, and confidence in learners who understand how to manage polarities and conflict and still make actionable decisions. In this context, it's also important to emphasize again the vital importance of developing a robust form of information and AI literacy, which equally relates to the next competency as well.

- Ability to Exercise Confidence and Sound Judgment: Closely connected to the ability to evaluate and use information is the willingness to exercise judgment and to do so confidently. This also connects to persistence because “The tasks left for humans in the age of smart machines generally are challenging. If we know clearly what to do in a situation, a smart machine can do it for us. So, productive human life in the future often will require confidence that persisting in an effort is worthwhile even if it does not immediately produce the desired outcome” (Lesgold 56, 2019). Confident judgment empowers us to courageously and willingly try to solve a problem; it demands from us grit and a growth mindset. Confident judgment also means remembering who is in the executive role and who is serving in an advisory capacity. Automation does not mean we surrender control to reckoning machines, but it takes confidence and sound judgment to know when to trust a machine versus when to say what we know to be right and true, regardless of the computational outputs (Smith xv-xix, 2019).

- Ability to Work Well with Machines: We’ve discussed at length the importance of this vital competency, one that Plato expressed skepticism over. I believe technological literacy and competence is possible, especially in the context of these other integral competencies, each of which complements and supports the others.

- Staying Physically and Mentally Fit: Lastly, in a technocentric world, the human body is often an afterthought. The irony, however, is that limitations in the development of artificially intelligent technology may be due to the fact that these intelligent machines lack a functioning, autonomous body. As one AI expert put it, “Thinking about the complexity and scale of the problem further, a seemingly inescapable conclusion for me is that we may also need embodiment” if we want AI to develop true intelligence (Karpathy, 2012). The body is inextricably linked to intelligence and to our minds, and this kind of total intelligence means we need to think about the total health of the human individual as well, especially in the age of intelligent machines (Potter 6, 2023). As one author claims, what is needed to be successful in this age is not new knowledge, per se, but extra brain power and cognitive bandwidth, and that kind of “complex thinking requires the body to be delivering more energy and oxygen to the brain, and that happens more successfully in healthy people” (Lesgold 59, 2019) Exercise, in other words, boosts brain power, which the research confirms: “Studies have shown that exercise produces chemicals that make it easier for new brain cells to communicate and that is one of the few things that can stimulate new brain cell growth in humans too, particularly in areas of the cortex vital for learning, memory and mood” (de Lange, 2023).

I do not disagree with Plato that powerful technologies can produce adverse effects. Social media is a good example of where we got it really, really wrong, especially in terms of the technology's effect on developing learners. My friend and frequent collaborator, Nate Green, wrote about this in Slate.

To get it right, we don't need to ask what can humans do better? versus what can machines do better? Instead we should be asking: what do humans need to learn and do in order to thrive in an age of artificial intelligence? Part of the answer is knowing how to work well with machines (we can do it, Plato!), which involves developing AI literacy, but to develop that literacy, we have look at all the integral competencies discussed above.

In my next post, I plan to turn my attention to the question of assessment in the Age of AI to answer the question: How do we leverage the human advantage to make human thinking visible in the age of cognitive technologies?

Sources:

- A large portion of this post was adapted from the following: Jared Colley. A People-Centered Organization Living in an AI World, Transformation R&D Report, Vol. 1. Ed. Dr. Brett Jacobsen, MV Ventures, Summer 2023. [Purchase and download a copy here]

- Plato. Phaedrus from The Collected Dialogues of Plato. Trans. R. Hackworth (1952). Eds. Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns. Princeton University Press, 2009.

- David Abram. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in the More-Than-Human World. Vintage Books, 2017.

- David De Cramer and Garry Kasparov. “AI Should Augment Human Intelligence, Not Replace It.” Harvard Business Review. Harvard Business Review Press, Winter 2021.

- Nada R. Sanders and John D. Wood. “The Secret to AI Is People.” Harvard Business Review. Harvard Business Review Press, Winter 2019.

- Melanie Mitchell. Artificial Intelligence: A Guide for Thinking Humans. Picador, 2019.

- A. Karpathy. “The State of Computer Vision and AI: We Are Really, Really Far Away.” Andrej Karpathy blog, 22 October 2012, karpathy.github.io/2012/10/

22/state-of-computer-vision. - Brian Cantwell Smith. The Promise of Artificial Intelligence: Reckoning and Judgment. The MIT Press, 2019.

- Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee. The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies. W. W. Norton & Co., 2014.

- H. James Wilson and Paul R. Daughtery. “Collaborative Intelligence: Humans and AI Are Joining Forces.” Harvard Business Review. Harvard Business Review Press, Winter 2021.

- Ruben R. Puentedura. “Transformation, Technology, and Education.” Strengthening Your District Through Technology Workshop, 18 August 2006. Accessed 14 March 2023. http://hippasus.com/resources/tte/.

- Kevin Kelly. The Inevitable: Understanding the Twelve Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future. Viking Press, 2016.

- Alan M. Lesgold. Learning for the Age of Artificial Intelligence: Eight Education Competences. Routledge Press, 2019.

- Zachary Stein. Education in a Time Between Worlds: Essays on the Future of Schools, Technology, and Society. Bright Alliance, 2019.

- James Bridle. Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for Planetary Intelligence. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022.

- Greg Toppo and Jim Tracy. Running with Robots: The American High School’s Third Century. The MIT Press, 2021.

- Catherine de Lange. "Mental Muscle," New Scientist, 3-9 June 2023.

- Ben Potter. Total Health: The Wholeness of People in an Age of Technology, Transformatino R&D Report, Vol. 2. Ed. Jared Colley, MV Ventures, Fall 2023. [Purchase and download a copy here]

- Nate Green. "Schools Really Messed Up With Social Media. Now, We Have a Second Chance," Slate, 26 June 2023. Accessed 25 October 2023. https://slate.com/human-interest/2023/06/mental-health-facebook-social-media-teenagers.html

Comments